Originally published on LOAM in April 2018

Making Natural Watercolors

A few weeks ago, I drove out to White Salmon, WA to take a workshop called ‘Making Natural Watercolors’ at Wildcraft Studio School. It had been several months since I’d driven through the Columbia River Gorge, and I was smitten, yet again, by its beauty. Sweeping evergreen panoramas, dramatic overlooks, the wide, sparkling river carving deep into the Cascades. As I neared Eagle Creek, there were stretches of road lined by blackened tree trunks, a sobering reminder of last summer’s devastating wildfires. It can be easy to forget, especially these days when we are nearly drowned here in Portland, that a few short months ago it was ash, not rain, falling from the sky.

I was grateful for the road trip out to White Salmon. It was the perfect way to begin a day of paint making—with a mind quieted by miles of scenic wilderness. When I arrived, the studio was set up with an array of paint making tools and materials. At the center was a series of bins filled with different colored minerals, lined up like a color spectrum.

For the vast majority of art history, back even before handprints were painted on the walls of the Lascaux Cave, natural pigments have been foraged from the earth, ground into powder, and mixed with some sort of binding agent to create paints. Our teacher, Scott Sutton, a local artist, educator, and expert pigment-hunter/paint-maker, explained that the process of making natural watercolors is very similar to that used to create natural oil or acrylic paints—it’s just a different medium to which the pigment is added. Our own watercolor medium consisted of gum arabic (hardened sap harvested from Acacia trees in Africa), honey, glycerin, and distilled water. Once prepared, it was like a viscous, liquid amber.

For the pigments, Scott showed us how to grind minerals to a powder with a mortar and pestle. Using a fine-mesh sieve, we sifted the particles onto a large piece of paper and returned any pebbles left behind to the mortar until they were properly pulverized. Once a pile of powdered pigment had accumulated, we transferred it to a large glass surface, added a splash of distilled water, and mixed it into a paste with a palette knife.

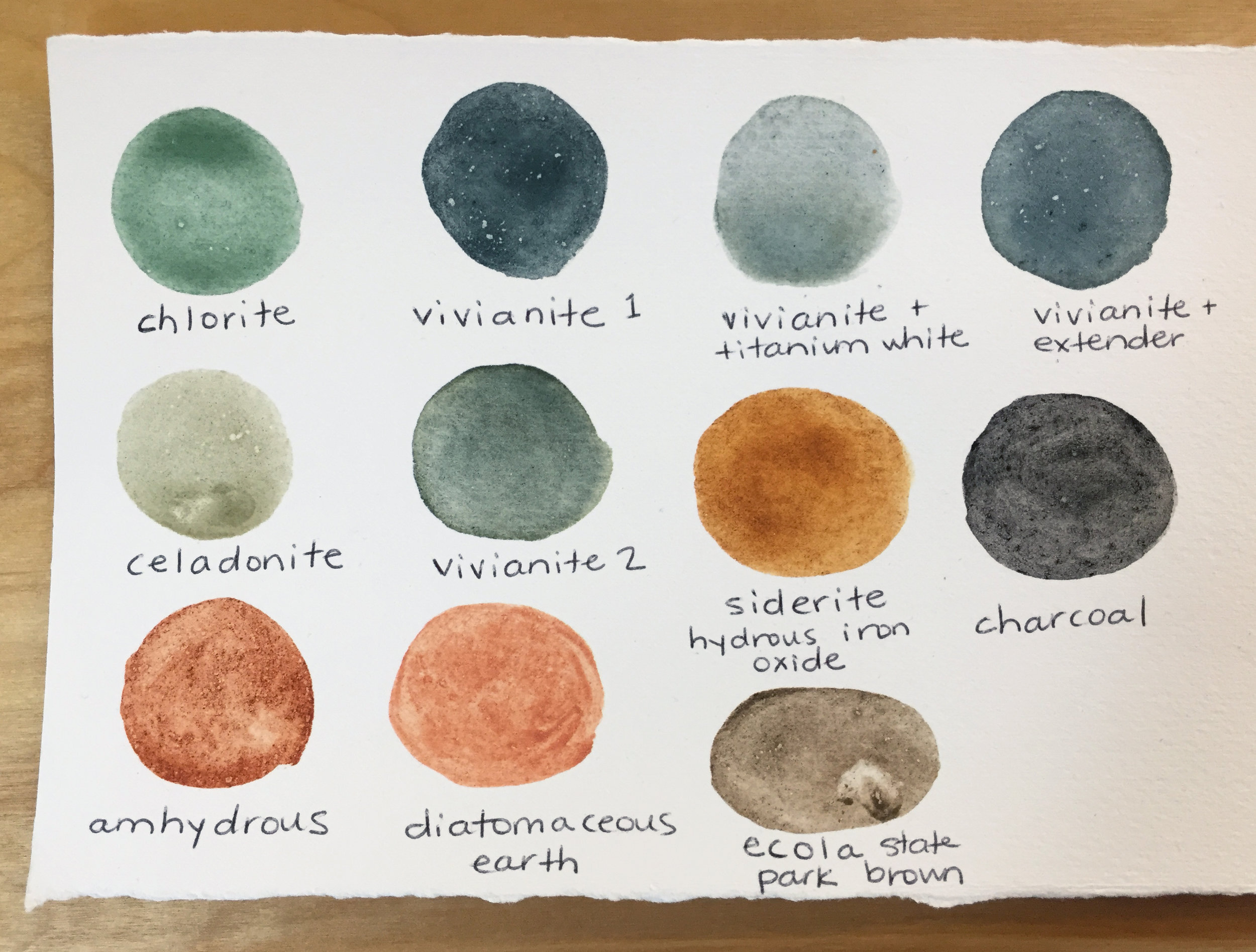

Finally, we combined the pigment with the watercolor medium using a tool called a glass muller, which looks kind of like a pestle but with a smooth, flat bottom. Moving the muller in a circular motion, we spread the paint thin across the glass in widening orbits, dispersing and dissolving the tiny particles of pigment into the medium. This part required a little elbow grease (too little grinding, and your paints will be gritty) but the process was oddly satisfying. When the consistency was just right, the paint was so smooth, like “room temperature butter,” as Scott put it. We listened carefully to the sound the muller made against the glass—like fine sandpaper at first and then smoother and smoother until the pigment was fully incorporated. At last, we got to experiment with the finished product, sweeping the freshly-made paints across different types of watercolor paper, and making ourselves color maps to remember the name of each mineral.

I loved learning the craft of paint making—getting lost in the flow of grinding and mixing and mulling. But what made the hands-on process even better was learning about the origins of the pigments themselves, each with its own unique chemical and geological history. Most of the minerals we worked with were harvested from Oregon and Washington, between the coast and the Cascades. Scott had collected them himself, with the help of geological maps, guidebooks, and a little luck. Once you start looking for pigments, he explained, you can’t help but see them. Along highways, riverbanks, the ocean—anywhere that erosion has exposed layers of previously hidden earth, there are likely to be some flashes of color.

Vivianite, one of the most magical minerals of the bunch, began forming hundreds of years ago after an earthquake triggered a tsunami on the Oregon coast. Stretches of shoreline littered with pinecones from Sitka spruce trees were completely buried. As time passed, elements in the soil like iron and phosphate, in combination with microorganisms, went to work on the pinecones, slowly replacing the organic matter with minerals. When Scott dug them up, they were still pinecone-shaped, some with distinct ridges, but they had been transformed into something else entirely. Breaking one open reveals a core of brilliant BLUE! Like a piece of gorgeously saturated sidewalk chalk. Secret treasures buried in the earth, just waiting to be cracked open.

Every one of the minerals had an incredible story. Diatomaceous earth, a brick red pigment, was buried under layers of lava flows, like a “vein of cooked earth.” Chlorite, which makes a lovely sea green paint, was carried through the water before being deposited alongside a waterfall at Mt. Hood. Celledonite, a lighter, celery-like green, was harvested from soil by the Sandy River. It’s the result of a volcanic eruption and was still covered in tiny sparkles of ash.

When I took out my watercolors earlier this week and made a few small paintings, I thought about the journeys these colors had made. My painting didn’t begin the moment I sat down and took out my brushes. It didn’t begin in White Salmon at Wildcraft Studio School, or when Scott hiked along the coast hunting for Vivianite, or when the tsunami came and buried the land, or when the Sitka spruce trees dropped their cones. The story of these paints is as old as the shapeshifting earth itself, my own role in it just the latest stop along an endless chain of transformations. Already, the paints have begun to fur over with mold, on the way to their next state (refrigeration and a few drops of clove oil would have helped prevent this). I wet my brush and dipped it into an earthquake, a tsunami, a volcano. I painted with rivers and waterfalls, deep soil and deep time. Bones, my own included, would turn blue with Vivianite if buried for long enough beside the pinecones.

On Saturday, I am taking a follow-up class with Scott Sutton at Wildcraft Studio School called ‘Foraging for Earth Pigments.’ This time, we will be lacing up our hiking boots and exploring the mountains, rivers, and creeks around Mt Adams and the Columbia River Gorge, learning to sustainably harvest natural pigments ourselves. Stay tuned for a recap in my next post!

Foraging for Earth Pigments

After learning how to make my own watercolors at Wildcraft Studio School a few weeks ago, I was hooked on natural pigments and eager to learn more. Fortunately, artist and piment-hunter Scott Sutton had another workshop coming up, this time an outdoor excursion called Foraging for Earth Pigments, and I jumped at the opportunity to backfill my new paint-making skills with the knowledge of how to collect pigments myself.

On Saturday, I drove out to Troutdale, Oregon, where I met up with Scott and the other students in our class. After a brief lesson on local geology (this portion of land had been flooded with basalt many times throughout history due to repeated volcanic eruptions), we grabbed our daypacks and carpooled the additional twenty minutes to the trailhead. In our backpacks we carried several large ziplock bags for harvesting, sharpies for labeling, journals for note-taking, small garden spades for digging, and lunches for eating. Before we had even left the trailhead, Scott ran across the street and came back with a handful of crumbly, red-brown soil. We gathered around and saw the way it smooshed like clay in his hands, staining them red. Our first pigment! Not a bad way to start.

The forest was overwhelmingly green as we set out down the trail. At this time of year, many months of rain have supercharged the flora. Soft, shaggy moss covers nearly every branch and trunk, giving everything a kind of alien-muppet vibe. Foraging for earth pigments would be an entirely different experience in, say, the desert, where the landscape is bald and the geology laid bare. In the Pacific Northwest, the plants are so dense that it takes quite a bit more detective work to determine what is going on beneath the surface.

Scott stopped us just a few dozen meters down the trail and pointed out a large tree trunk whose roots had pulled up from the earth, revealing more reddish, clay-like soil. It’s places like this that we need to learn to pay attention to. When I hike, I’m accustomed to noticing the trees, the plants, the wildflowers, the stretch of trail directly in front of my feet. It takes some conscious adjustment to scan for subtle variations in rock and exposed soil. Throughout the day, we begin to add names like basalt, sandstone, and mudstone to our vocabularies. There’s something about having the words that helps bring these things into focus.

A ways down the trail, we paused again, this time beside a little creek. Here, Scott bent down, picked up a small yellow rock, and performed a ‘scratch test.’ It melted beautifully against a nearby wet stone, scribbling out a thick coating of yellow ochre. There were audible oohs and ahhs from the group, and we quickly went about gathering the yellow ourselves, testing each piece before dropping it into our ziplock bags. The richness of the yellow ochre color and its abundance here in the creek, something we would have walked right by the day before, had us giddy. It felt like unlocking a secret. Stumbling upon a gift. Free art supplies! Just lying here on the ground!

Continuing on, we scrambled over fallen logs, took a detour to a roaring waterfall, waded through Jurassic Park-like ferns, and squelched through boot-stealing mud on our descent to the banks of the Sandy River. When we reached our final destination, Scott remarked on how high the water levels were due to recent rain. There was much less beach and many more rapids that anticipated. Still, we were able to find a good spot to stop for lunch and explore what turned out to be the most abundant foraging site of the day. It was a pigment bonanza.

By the river, there were deposits of clay-like Celadonite all over, in different shades of green. It was soft and crumbly, easy to gather by hand. One of my favorite finds was a piece of Celadonite that was gray-green on the outside but, broken open, revealed veins of deep blue, glittering with specks of volcanic ash. That one made it into my bag for sure, although I suspect it will be difficult to isolate the blue from the rest.

Suffice it to say, our backpacks were a lot heavier on the way up than on the way down. We were laden with colors. An embarrassment of riches. One of the students, who was visiting from Phoenix, wondered about checking a bag of rocks on her return flight (#pigmentforagerproblems).

When I got home, I carefully rinsed and separated my pigments, having made the beginners mistake of loading them all into one bag. I lined a couple of cookie sheets with paper towels and laid them out to dry, organized by color. Upstairs in my art studio, I have whole tupperware containers filled with store-bought paint—acrylics and watercolors in every imaginable hue. And don’t get me wrong, I love me a full-spectrum rainbow of paints, fluorescents included, but I’ve never cared about those factory-made paints the way I care about these little colored rocks laid out on my kitchen counter. I find myself handling them so gently, checking on them as they dry, carefully arranging them in groups of the same, like little pigment families. They feel so precious, these colors that formed deep in the forest, deep in the earth, that I gathered with stained fingertips and carried on my back and then the passenger seat of my car, all the way from their home to mine.

In Victoria Finlay’s book Color: A Natural History of the Palette, she writes about how “colormen first appeared in the mid-seventeenth century, preparing canvases, supplying pigments, and making brushes.” Their arrival was a sign of how “the act of painting was moving from a craft profession to an art one. For ‘craftspeople’ the ability to manage one’s materials was all important; for ‘artists’ the dirty jobs of mixing and grinding were simply time-consuming obstacles to the main business of creation...Slowly and irrevocably, artists began to push their porphyry pestles and mortars to the backs of their workshops, while professional colormen...did the grinding.”

This separation of ‘craft’ and ‘art’ is even more true today, when any of us can walk into an art supply store and find a selection of hundreds of different paints, each with details about its relative opacity, viscosity, etc. Foraging for earth pigments is a real commitment. Between traveling and trekking and grinding and preparing your medium, you’ve logged some long hours before even making the first mark on your canvas. Today, anyone can make a painting at a moment’s notice. It’s amazing, really, what we have access to. And more accessibility means more art made by more people, which is always a wonderful thing. And yet, as Finlay puts it, “not really knowing what these paints are or where they have come from, one is somehow alienated from the process of making them into art.” There’s a feeling of reverence, a deeply satisfying connection to the land, that can only be found opting for the slower, more scenic route.

Increased interest in natural pigments, thanks in no small part to those who have made them cool on social media, parallels similar movements in other industries like ‘slow food’ and ‘slow fashion’ that are working to bridge the disconnect between products and consumers. What does it look like to make a painting that is “local”? What does it look like to harvest pigments sustainably and respectfully? Are we willing to work with a limited palette? Are we willing to put the ‘craft’ back in our art practice, even if that slows us down? At the very least, a hike in the woods, a trip to the source with open eyes, seems like a good place to start.